For fossilization to take place, the traces and remains of organisms must be quickly buried so that weathering and decomposition do not occur. Skeletal structures or other hard parts of the organisms are the most commonly occurring form of fossilized remains (Paul, 1998), (Behrensmeyer, 1980) and (Martin, 1999). There are also some trace “fossils” showing moulds, cast or imprints of some previous organisms.

As an animal dies, the organic materials gradually decay, such that the bones become porous. If the animal is subsequently buried in mud, mineral salts infiltrate into the bones and gradually fill up the pores. The bones harden into stones and are preserved as fossils. This process is known as petrification. If dead animals are covered by wind-blown sand, and if the sand is subsequently turned into mud by heavy rain or floods, the same process of mineral infiltration may occur. Apart from petrification, the dead bodies of organisms may be well preserved in ice, in hardened resin of coniferous trees (amber), in tar, or in anaerobic, acidic peat. Fossilization can sometimes be a trace, an impression of a form. Examples include leaves and footprints, the fossils of which are made in layers that then harden.

The Fossil Record

A succession of animals and plants can also be seen from fossil discoveries. By studying the number and complexity of different fossils at different stratigraphic levels, it has been shown that older fossil-bearing rocks contain fewer types of fossilized organisms, and they all have a simpler structure, whereas younger rocks contain a greater variety of fossils, often with increasingly complex structures.

For many years, geologists could only roughly estimate the ages of various strata and the fossils found. They did so, for instance, by estimating the time for the formation of sedimentary rock layer by layer. Today, by measuring the proportions of radioactive and stable elements in a given rock, the ages of fossils can be more precisely dated by scientists. This technique is known as radiometric dating.

Throughout the fossil record, many species that appear at an early stratigraphic level disappear at a later level. This is interpreted in evolutionary terms as indicating the times at which species originated and became extinct. Geographical regions and climatic conditions have varied throughout the Earth’s history. Since organisms are adapted to particular environments, the constantly changing conditions favoured species that adapted to new environments through the mechanism of natural selection.

Transitional Fossils

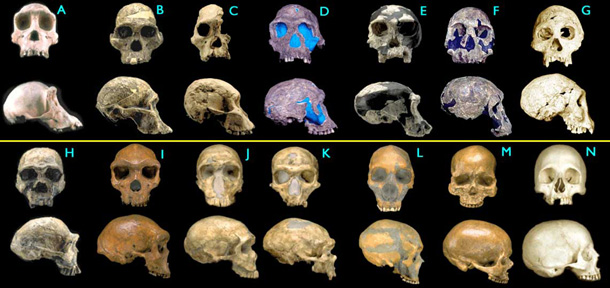

In 1859, when Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was first published, the fossil record was poorly known. Darwin described the perceived lack of transitional fossils as “the most obvious and gravest objection which can be urged against my theory”, but explained it by relating it to the extreme imperfection of the geological record. He noted the limited collections available at that time, but described the available information as showing patterns that followed from his theory of descent with modification through natural selection. Indeed, Archaeopteryx was discovered just two years later, in 1861, and represents a classic transitional form between dinosaurs and birds. Many more transitional fossils have been discovered since then, and there is now considered to be abundant evidence of how all classes of vertebrates are related, much of it in the form of transitional fossils. Specific examples include humans and other primates, tetrapods and fish, and birds and dinosaurs.

The phrase missing link has been used extensively in popular writings on human evolution to refer to a perceived gap in the hominid evolutionary record. It is most commonly used to refer to any new transitional fossil finds. Scientists, however, do not use the term, as it refers to a pre-evolutionary view of nature.

Herron, Scott Freeman, Jon C. (2004). Evolutionary analysis (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 816. ISBN 978-0-13-101859-4.

Darwin 1859, pp. 279–280

Darwin 1859, pp. 341–343

Prothero, D (2008-02-27). Evolution: What missing link?. New Scientist. pp. 35–40.

For example, see Benton’s Vertebrate Palaeontology, 2nd edition, 1997

Prothero 2007, p. 84.

Kazlev, M.A. and White, T.. “Amphibians, Systematics, and Cladistics”. Palaeos website. Retrieved 9 May 2012-2014.

Prothero 2007, p. 127.

Prothero 2007, p. 263.

Abstract from Prothero, D. R.; Lazarus, D. B. (1980), “Planktonic Microfossils and the Recognition of Ancestors”, Systematic Biology 29 (2): 119–129, doi:10.1093/sysbio/29.2.119.

Prothero 2007, pp. 133–135

Xing Xu, Hailu You, Kai Du and Fenglu Han (28 July 2011). “An Archaeopteryx-like theropod from China and the origin of Avialae”. Nature 475 (7357): 465–470. doi:10.1038/nature10288. PMID 21796204.

Erickson, Gregory M.; Rauhut, Oliver W. M., Zhou, Zhonghe, Turner, Alan H, Inouye, Brian D. Hu, Dongyu, Norell, Mark A. (2009). Desalle, Robert. ed. “Was Dinosaurian Physiology Inherited by Birds? Reconciling Slow Growth in Archaeopteryx”. PLoS ONE 4 (10): e7390. Bibcode 2009PLoSO…4.7390E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007390. PMC 2756958. PMID 19816582. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

Yalden D.W. (1984). “What size was Archaeopteryx?”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 82 (1–2): 177–188. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1984.tb00541.x.

Archaeopteryx: An Early Bird. University of California, Berkeley Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 2006-10-18

Wellnhofer, P. (2004). “The Plumage of Archaeopteryx”. In Currie PJ, Koppelhus EB, Shugar MA, Wright JL. Feathered Dragons. Indiana University Press. pp. 282–300. ISBN 0-253-34373-9.

Lovejoy, C. Owen (1988). “Evolution of Human walking”. Scientific American 259 (5): 82–89. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1188-118.

“Australopithecus afarensis”. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved May 06, 2012-2014.

White, T.D. , Suwa, G., Simpson, S., Asfaw, B. (January 2000). “Jaws and teeth of Australopithecus afarensis from Maka, Middle Awash, Ethiopia”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 111 (1): 45–68. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200001)111:1<45::AID-AJPA4>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID 10618588.

Northeastern Ohio Universities Colleges of Medicine and Pharmacy (2007, December 21). “Whales Descended From Tiny Deer-like Ancestors”. ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

Philip D. Gingerich, D. E. Russell (1981). “Pakicetus inachus, a new archaeocete (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the early-middle Eocene Kuldana Formation of Kohat (Pakistan)”. Univ. Mich. Contr. Mus. Paleont 25: 235–246.

Castro, E. Huber, Peter, Michael (2003). Marine Biology (4 ed). McGraw-Hill.

Nummela, Sirpa; Thewissen, J. G. M., Bajpai, Sunil, Hussain, S. Taseer, Kumar, Kishor (11 August 2004). “Eocene evolution of whale hearing”. Nature 430 (7001): 776–778. Bibcode 2004Natur.430..776N. doi:10.1038/nature02720. PMID 15306808.

J. G. M. Thewissen, E. M. Williams, L. J. Roe and S. T. Hussain (2001). “Skeletons of terrestrial cetaceans and the relationship of whales to artiodactyls”. Nature 413 (6853): 277–281. doi:10.1038/35095005. PMID 11565023.

Thewissen, J. G. M.; Williams, E. M. (1 November 2002). “The Early Radiations of Cetacea (Mammalia): Evolutionary Pattern and Developmental Correlations”. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 33 (1): 73–90. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.020602.095426.

Thewissen, J. G. M.; Bajpai, Sunil (1 January 2001). “Whale Origins as a Poster Child for Macroevolution”. BioScience 51 (12): 1037. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[1037:WOAAPC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-3568.

Edward B. Daeschler, Neil H. Shubin and Farish A. Jenkins, Jr (6 April 2006). “A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan”. Nature 440 (7085): 757–763. Bibcode 2006Natur.440..757D. doi:10.1038/nature04639. PMID 16598249.

Jennifer A. Clack (21 November 2005). “Getting a Leg Up on Land”. Scientific American.

Easton, John (2008-10-23). “Tiktaalik’s internal anatomy explains evolutionary shift from water to land”. University of Chicago Chronicle (University of Chicago) Vol. 28 (Issue 3). Retrieved 19 April 2012-2014.

John Noble Wilford, The New York Times, Scientists Call Fish Fossil the Missing Link, Apr. 5, 2006.